This class considers land and nutrient resources available for agriculture, paralleling the inventory approach to water resource assessments taken in Class 3. Although remote observations taken from space have revolutionized our knowledge of land use patterns and trends, it is still difficult to distinguish specific crops, estimate crop yields, or evaluate soil fertility using remote sensing alone. Ground-based observations are needed to validate remote sensing data, which are more extensive but less accurate. Some preliminary assessments of agricultural land use are presented in the class readings and in S8.

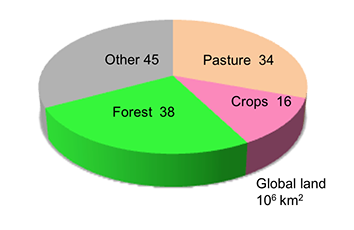

Lambin and Meyfroidt (2011) rely on land use estimates obtained from a variety of sources to construct global land budgets for 2000 and 2030. They indicate that current crop land and pasture together use about 40% of global ice-free land. Much of the remaining land is unsuitable for agriculture or in tropical forest regions where extensive agricultural development could be unsustainable and contribute to climate change. The Lambin and Meyfroidt analysis suggests that the additional land suitable for rural and urban needs is about 5% of currently used land. The most favorable options for land expansion are unprotected sparsely populated savannahs in South America and Africa. In some areas it may be possible to convert currently unsuitable land to agricultural uses if there is extensive investment in infrastructure and soil improvement, but these measures may not be economically feasible at current food prices. Some context is provided in S7, which briefly discusses recent cropland expansion from deforestation.

Zabel et al. (2014) provide an alternative model-based approach for identifying land suitable for agriculture. They consider soil, terrain, and climate in an analysis that maps areas that can support particular food, feed, and energy crops. Their analysis indicates that only about 10% of the global land suitable for some form of agriculture is still available for cultivation. Both Lambin and Meyfroidt (2011) and Zabel et al. (2014) suggest that we have nearly used up the global supply of agriculturally suitable land, although there may be room for some cropland expansion in particular regions. It may be more efficient and environmentally acceptable to increase production by redistributing crops to make better use of currently available land and water resources (see Class 10).

© Source unknown. All rights reserved. This content is excluded from our Creative Commons license.

For more information, see https://ocw.mit.edu/help/faq-fair-use.

Tilman et al. (2000) discuss the role of biofuels, which may compete with food crops for land and other natural resources. They argue that biofuel development can be based on feedstocks that avoid such competition while still providing cost–effective energy. Their discussion complements the mass balance analysis of Alexander et al. (2017) presented in Class 2.

Fixen (2009) estimates global supplies of three key soil nutrients (nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium) required for crop production. The supplies of all three appear to be sufficient until at least 2050 but these nutrients are sometimes not readily available to farmers, especially poor farmers, in the areas where they are most needed. Also, significant increases in the quantities of nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizer applied to crops are likely to have adverse environmental effects, especially on downstream ecosystems and water bodies (see Class 6).

Required Readings

Land Use

-

Eric F. Lambin and Patrick Meyfroidt. 2011. "Global Land Use Change, Economic Globalization, and the Looming Land Scarcity." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 108, no. 9: 3465–72.

Identification of Land Suitable for Crops

Florian Zabel, Birgitta Putzenlechner, and Wolfram Mauser. 2014. "Global Agricultural Land Resources—A High Resolution Suitability Evaluation and Its Perspectives until 2100 under Climate Change Conditions." PloS One. 9, no. 9: e107522.

Biofuels

David Tilman, Robert Socolow, et al. 2009. "Beneficial Biofuels—The Food, Energy, and Environment Trilemma." Science. 325, no. 5938: 270–271.

Nutrient Supplies

Paul E. Fixen and Adrian M. Johnston. 2009. "World Fertilizer Nutrient Reserves: A View to the Future." Better Crops with Plant Food. 93, no. 3: 8–11.

Optional Reading

Cropland Expansion

E.F. Lambin, H.K. Gibbs, et al. 2013. "Estimating the World's Potentially Available Cropland Using a Bottom-Up Approach." Global Environmental Change. 23, no. 5: 892–901.

Land Use Alternatives

Joern Fischer, Berry Brosi, et al. 2008. "Should Agricultural Policies Encourage Land Sparing or Wildlife-Friendly Farming?" Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. 6, no. 7: 380–385.

Biofuels

Tim Searchinger and Ralph Heimlich. 2015. "Avoiding Bioenergy Competition for Food Crops and Land." Working Paper, Installment 9 of Creating a Sustainable Food Future. World Resources Institute.

Crop Suitability

IIASA, FAO. 2012. "Global Agro-Ecological Zones—Model Documentation (GAEZ v. 3.0)." International Institute of Applied Systems Analysis & Food and Agricultural Organization, Laxenburg, Austria & Rome, Italy.

Discussion Points

- How could you determine the potential for converting pasture land currently used for grazing or feed to cropland? For context, recall that the existing pasture land area is significantly larger than cropland area. Why do you think the conversion of pasture land to cropland is not discussed in our readings as an option for increasing crop production?

- Do you believe that biofuels can be grown on land that is not suitable for food crops? What technological advances do you think need to be made for this to be possible (consult the optional reading by Searchinger and Heimlich)?

- How can we trade off the disadvantages of deforestation with the advantages of being able to use deforested land to grow more food?