Contents:

- Lab Basics

- First Day: Lab Orientation

- Module 1: RNA Engineering

- Module 2: Protein Engineering

- Module 3: Cell-Biomaterial Engineering

Lab work is divided into three modules of eight sessions each. Learning materials for each lab session (linked below under 'Lab Materials') include an introduction, experimental protocol, and a reagents list, followed by a "for next time" homework assignment. A short pre-lab lecture preceeds most of the lab sessions.

Selected results from some labs are included courtesy of the students and used with permission.

Lab Basics

| WORKING IN THE LAB | COMMUNICATING YOUR WORK |

|---|---|

|

General lab policies, do's and don'ts Guidelines for working in the tissue culture facility Guidelines on using personal protective equipment, developed by

|

Statement on Collaboration and Integrity Guidelines for maintaining your lab notebook |

First Day: Lab Orientation

There are ten stations for you and your lab partner to visit on your lab tour today. Some will be guided tours with a TA or faculty there to help you and others are self-guided, leaving you and your partner to try things on your own. Your visit to each station should last ~10-15 minutes. It doesn't matter which station you visit first but you must visit them all before you leave today. Afterward, you should have some time remaining to begin the For Next Time assignment, and are strongly encouraged to do so. Your lab practical next time will assess your mastery of a selection of these stations - all are fair game, as is the lab safety material covered in today's pre-lab lecture.

| PRE-LAB LECTURE | LAB Materials |

|---|---|

| (PDF) | Lab orientation |

Module 1: RNA Engineering

Instructors: Jacquin Niles and Agi Stachowiak

In this module you will investigate RNA aptamer selection. You may already be familiar with peptides or proteins, such as antibodies, that bind to specific molecules. Short fragments of RNA – called RNA aptamers - can have secondary structures that also allow them to bind a target molecule with good affinity and specificity. Normally, RNA aptamers that bind particular targets are found by screening many candidates at random in a process called SELEX, or systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment; however, predictive computational tools can also be used. In the coming weeks, you will essentially perform one round of SELEX. Because SELEX typically takes several rounds to isolate target-binding aptamers, you will start with a known aptamer mixture rather than than a completely random library. Your goal will be to explore what experimental parameters affect the enrichment of a heme-binding RNA aptamer from a mixture of heme-binding and non-binding RNAs.

Acknowledgement: We thank 20.109 instructor Natalie Kuldell for helpful discussions and for acquiring funding for module development.

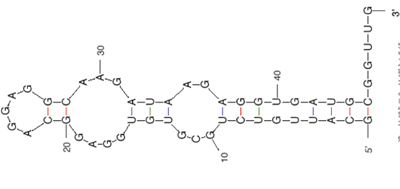

Public domain image. (Prepared using RNA Folding (mfold) at the mFold Web Server). Reference: Zuker, M. "Mfold Web Server for Nucleic Acid Folding and Hybridization Prediction." Nucleic Acids Res. 31, no. 13 (2003): 3406-3415.

| MODUle 1: RNA Engineering | ||

|---|---|---|

| LAB DAYS | PRE-LAB LECTURES | LAB Materials |

| Day 1 | (PDF) | Amplify aptamer-encoding DNA |

| Day 2 | (PDF) | Purify aptamer-encoding DNA |

| Day 3 | (PDF) | Prepare RNA by IVT |

| Day 4 | (PDF) | Purify RNA and run affinity column |

| Day 5 | (PDF) | RNA to DNA by RT-PCR |

| Day 6 | (PDF) | Post-selection IVT and journal club |

| Day 7 | (PDF) | Aptamer binding assay |

| Day 8 | Journal club (contd.) | |

See the Assignments page for descriptions of the Module 1 laboratory report and RNA computational analysis assignments.

Module 2: Protein Engineering

Instructors: Alan Jasanoff and Agi Stachowiak

In this experiment, you will modify a protein called inverse pericam (developed by Nagai, et al.) in order to affect its functions as a sensor. Inverse pericam (IPC) comprises a permuted fluorescent protein linked to a calcium sensor. The "inverse" in the name refers to the fact that this protein shines brightly in the absence of calcium, but dimly once calcium is added. The dissociation constant KD of wild-type IPC with respect to calcium is reported to be 0.2 μM (see also figure below). Your goal will be to shift this titration curve or change its steepness by altering one of the calcium binding sites in IPC's calcium sensor portion. You will modify inverse pericam at the gene level using a process called site-directed mutagenesis, express the resultant protein in a bacterial host, and finally purify your mutant protein and assay its calcium-binding activity via fluorescence. In the course of this module, we will consider the benefits and drawbacks of different approaches to protein design, and the types of scientific investigations and applications enabled by fluorescently tagged biological molecules.

Reference: Nagai, T., et al. "Circularly Permuted Green Fluorescent Proteins Engineered to Sense Ca2+." PNAS 98, no. 6 (March 6, 2001): 3197-3202. [Open Access]

We gratefully acknowledge 20.109 instructor Natalie Kuldell for helpful discussions during the development of this module, as well as for her prior work in developing a related module in the Spring 2007 course.

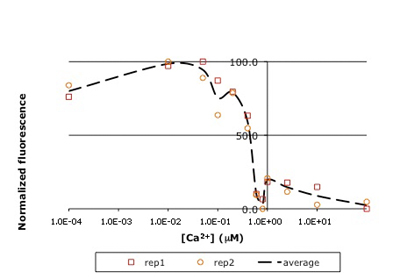

Raw titration curve for IPC. Shown here is sample data from the teaching lab: normalized fluorescence for wild-type inverse pericam as a function of calcium concentration. As you will later learn, an apparent KD can be estimated from such a plot: it is the point on the x-axis where the curve crosses y = 50%, or ~0.5 μM here

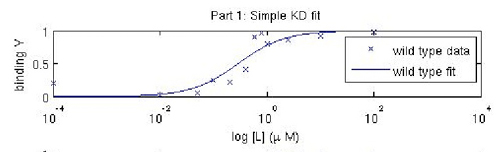

Fitted titration curve for IPC. A more sophisticated analysis using curve-fitting reveals KD to be ~ 0.3 μM, closer to the reported value for inverse pericam.

| Module 2: Protein Engineering | ||

|---|---|---|

| LAB DAYS | PRE-LAB LECTURES | LAB Materials |

| Day 1 | (PDF) | Start-up protein engineering |

| Day 2 | (PDF) | Site-directed mutagenesis |

| Day 3 | (PDF) | Bacterial amplification of DNA |

| Day 4 | (PDF) | Prepare expression system |

| Day 5 | (PDF) | Induce protein and evaluate DNA |

| Day 6 | (PDF) | Characterize protein expression |

| Day 7 | Assay protein behavior | |

| Day 8 | Data analysis | |

See the Assignments page for a description of the Module 2 protein engineering research paper.

Module 3: Cell-Biomaterial Engineering

Instructor: Agi Stachowiak

What makes a cell become one type and not another? How can we influence this process, and why would we even want to? When faced with conflicting information – in our own experiments, or in the broader scientific literature – how do we determine what is credible? These are just some of the questions you will explore in the third and final module, all in the context of tissue engineering. The goal of tissue engineering (also called regenerative medicine) is to repair tissues damaged by acute trauma or disease. Repair is stimulated by insertion of a porous scaffold at the wound or disease site; the scaffold may carry relevant mature or progenitor cells, and in some cases also soluble growth factors. In cartilage tissue, mature cells are called chondrocytes, and their progenitor cells are mesenchymal stem cells. Tissue regeneration shares many characteristics with natural tissue development, including the importance of appropriate cell differentiation and phenotype maintenance. You will perform a hypothesis-driven investigation of the effects of environmental manipulations on primary chondrocytes and/or mesenchymal stem cells. In particular, you will assess cell viability, genotype, and protein production, but the specific experimental question is up to you.

I gratefully acknowledge Professor Alan Grodzinsky and several members of his lab group (particularly Rachel Miller and Paul Kopesky), for their technical advice and stimulating discussions during the development of this module.

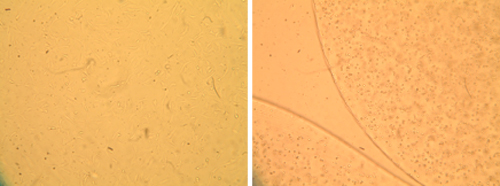

Morphology of primary bovine chondrocytes grown under two different culture conditions. Optical micrographs of chondrocytes grown in monolayer (left) and alginate bead culture (right) are shown. Cells in the 3D culture retain a round phenotype, while cells on the flat surface extend processes and spread out.

| Module 3: Cell-Biomaterial Engineering | ||

|---|---|---|

| Lab DAYS | PRE-LAB LECTURES | LAB Materials |

| Day 1 | (PDF) | Start-up biomaterials engineering |

| Day 2 | Initiate cell culture | |

| Day 3 | (PDF) | Testing cell viability |

| Day 4 | (PDF) | Preparing cells for analysis |

| Day 5 | (PDF) | Transcript-level analysis |

| Day 6 | (PDF) | Protein-level analysis |

| Day 7 | (PDF) | Wrap-up analysis |

| Day 8 | Student presentations | |

See the Assignments page for a description of the Module 3 cell-biomaterial engineering report.